One of Memphis’ most beloved individuals is radio, television, and master of ceremonies personality, George Klein. George has broadcasted over the Memphis airwaves since the early 1950s just before rock ‘n’ roll was born and soon thereafter became the most popular disc jockey. For a twelve-year period he also hosted one of the most watched televisions shows in Memphis. Throughout the years, he has been a visible figure as an MC at many public events, often raising large amounts of money for charitable causes. He also was one of Elvis Presley’s closest friends from their first meeting in the eighth grade in 1948, through their parallel careers, until Elvis’ death in 1977.

Today, George divides his time as a VIP host at the Horseshoe Casino in Tunica, Mississippi, continues to MC various events, and broadcasts his radio show in Memphis. His radio show now reaches a national audience through Sirius satellite radio.

I met George on January 16, 2004, for a couple of hours one afternoon in Memphis to talk about his career and other projects, Elvis, and rock ‘n’ roll.

JP: The first topic I want to ask you about is your career as a DJ here in the Memphis area. Your first radio job was in Osceola, Arkansas, while you were attending Memphis State University [now known as the University of Memphis].

GK: Basically what happened was I came out of high school, went to Memphis State, and then developed this great interest in radio. I knew couldn’t go to college and go to radio school at the same time so I did what a lot of guys did in those days. I just hung around radio stations. I’d go in and do anything I could do whether it was be an errand boy, gopher, what have you. When I was in high school, I was sports editor of my newspaper, as well as being editor, and I was working with one of the announcers. The guy was doing play by play on football and he would have a kid from each high school to be his spotter at the games to tell him who made the tackles and who did all this jazz.

Well, I did a pretty good job so one day I got a call from this guy and he said, “George, I’m transferring over to WHBQ. Do you want to come over and do recreations of baseball games – the Memphis Chicks baseball team? I won’t travel with them on the road but I’ll recreate them here.” You know, Ronald Reagan did that. That’s how he got into radio, remember? What happens is they do the local games live in Memphis, but they don’t go on the road – back in those days it was too expensive. So they would have a Western Union guy at the baseball stadium and he would sit there at the game and say, “Johnny Jones is up. Strike One. Strike Two. He swings at the next pitch. Flies out to center field. One out.” That’s all that would come across the machine. So he would teletype that back to this radio station. I would be like where you are and pulling it off the machine. The announcer would be over here and he’d have a picture of the ballpark and then he would have different sound effects. It was kind of neat. He’d take his billfold and he’d slap it with a ruler to make the sound of a guy catching the ball. If it was a hit, he’d have a block of wood and a mallet and he’d hit that and say, “He swings and he hits and his ball is going out to center field.”

JP: It was more like doing a show like Orson Welles.

GK: Yeah, a baseball recreation was what it was called. So I’d take this stuff off the machine and edit for the announcer and hand it to him. Then I’d run and get him coffee and donuts – stuff like that. Then when I got off the air – by this time I’m a sophomore in college – the program director came to me and said to me, “Dewey Phillips* is on the air from 9 p.m. until midnight. He follows the baseball games which usually run from about 7 until 9 and Dewey would come on at nine. This is in the summertime. In the winter time when there was no baseball, he’d come on 7 to midnight. So we need someone to babysit Dewey because he’s a wild and crazy disc jockey. He’s not your orthodox disc jockey.

[*Dewey Phillips (no relation to Sun Records’ Sam Phillips) was the first disc jockey to play an Elvis Presley record. On the night of July 7, 1954, Dewey Phillips played Elvis Presley’s first record, That’s All Right/Blue Moon of Kentucky on his Red Hot and Blue show broadcasted from WHBQ in Memphis. The result was orders totaling 7,000 copies for a record, the product of many weeks work, which was finally released on July 19, 1954.]

JP: Was any rock ‘n’ roll out by that time?

GK: It was just rhythm and blues. No. Elvis hadn’t hit yet. Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Bo Didley, Little Richard, all those guys. The Drifters, the Platters. So the ballgame would end. I’d go over and sit with Dewey. I’d answer his telephone. He’d get a lot of requests. A lot of people would call wanting him to play this, play that. I’d write it down and say, “Dewey, they want to hear this,” and he’d play it. So I became friends with Dewey. And then when baseball season ended, I stayed on. I’d come up at 9 o’clock and do the same thing. I did that for about a year.

Well, I knew that I had to get some real experience if I wanted to get into radio. I couldn’t just be a gopher like that. But one lucky thing was that I had access to the tape machines. So while Dewey was on, I’d go down in the studio and I’d get me some news off the news wire or I’d do commercials, and I’d practice myself. Then I’d have someone listen to me and tell me what I was doing wrong. So, anyway, the summer was coming up, and I think the ball games had switched to another station, so I told Dewey, “Dewey, look. I’ve got to get some experience, man.” So I sent out tapes. I made up what they call raw audition tapes. Like I was really on the air, but I wasn’t. It was an audition. You assimilate as you’re on the air. So I sent them to Blytheville, Osceola, Jackson, Hot Springs, everywhere.

Well, I knew that I had to get some real experience if I wanted to get into radio. I couldn’t just be a gopher like that. But one lucky thing was that I had access to the tape machines. So while Dewey was on, I’d go down in the studio and I’d get me some news off the news wire or I’d do commercials, and I’d practice myself. Then I’d have someone listen to me and tell me what I was doing wrong. So, anyway, the summer was coming up, and I think the ball games had switched to another station, so I told Dewey, “Dewey, look. I’ve got to get some experience, man.” So I sent out tapes. I made up what they call raw audition tapes. Like I was really on the air, but I wasn’t. It was an audition. You assimilate as you’re on the air. So I sent them to Blytheville, Osceola, Jackson, Hot Springs, everywhere.

Well this guy called me from Osceola and he said, “I got your tape. Can you come over?” I didn’t even have a car. I had to ride a bus over there. So then I got the job. He thought I was going to work full-time, but I knew to myself that I was going to come back and go my senior year in college. I didn’t want to blow that off after three years. Because I told him I was going to be full-time. But, man, I got some great experience, Joe. You know, in a small station, you do everything. And I was fifty miles from Memphis so once in a while the signal would skip and people in Memphis could hear me. My friends said if they tried real hard, they could find me on the dial. So I went over there for about three and a half – four months and then I told the guy, I said look I’ve got to go back to college.

So I came back to Memphis and while I was going to Memphis State my senior year, I got a part-time job at KWAM Radio. It’s 990AM on the dial in Memphis which was a country station. I was there working weekends. And then, as I started approaching the middle of my senior year, the morning guy left. Back in those days, they had what they call block programming. In the morning, they had a rhythm and blues show. In the mid-day and afternoon, they had an easy country show and then they signed off at sun down. So I started doing the morning show. And man, back in those days, we didn’t take the [market share] ratings because it was a small station. The ratings – I mean – the mail started coming in and I’m not exaggerating, I was getting 25 to 35 letters a day which was a lot for people to sit down and write you a letter.

JP: And you were just starting out.

GK: Well, I had been on the fringes of it, but this is my first real show as George Klein. So I’m on the air and I develop this bop-talking style – I talked in rhymes:

“DJ, the GK,

on the scene

with the record machine

coming your crazy way

on a Monday.

Man, I’m here.

Have no fear

Just lend me your ear . . .”

Stuff like that because I knew that you had to talk the language. It’s sort of like a hip-hop guy today. If you talk that street language right, they zero in on you. So the kids zeroed in on me because they knew I was hip.

JP: Where were you picking up all of the lingo?

GK: Just off the street. I was hanging out everywhere. You know, I was young. I was like 20, 21. And I was everywhere. So I got hot, man. I then got a call from WMC, the big station in town and the guy said – and I had known him because he had been at WHBQ one time as general manager – he said, “Look, you’ve got that little radio show over there at KWAM?” I said, “Yes, sir.” He said, “You know what your ratings are?” I said, “No, sir. They don’t take ratings over here.” He said, “What are you doing when you get off the air today?” I said, “Nothing.” He said, “Come up and see us and let’s have coffee.”

So I went up and he pulled out the ratings. I was like number 2 or 3 in the market in the morning and I didn’t even know it. He said, “Look at these ratings.” I said, “Gee, I didn’t even know it.” He said, “You’re red hot. You want to come over here and work.” I said, “This is an easy listening station, a middle of the road station.” He said, “No, rock ‘n’ roll is coming in. We’re going to put you on in the afternoon and call it The George Klein Rock ‘n’ Roll Ballroom Show.” So I went over there for about like triple my salary because I was only making about, back in those days, I probably was making $65 to $70 a week was all. And I went over there for like about $150 to $170. So I thought that was all the money in the world.

JP: How long had you been at KWAM when this happened?

GK: I was on the air for about six months in the morning.

JP: Wow. You were making an impression quickly.

GK: Well, I was in tune, Joe, with what was going on. It’s like the young guy that’s in tune with music today. But by the same token, I stayed on top of it and I did my homework. I still practiced my delivery and all that jazz because I really wasn’t a good announcer. I was a rock ‘n’ roll disc jockey. Talking in rhythms and rockin’ and rollin’. And I wasn’t polished like a straight announcer. I wasn’t like that yet.

JP: It seems to me what you were tapping onto something that the normal radio announcer wasn’t doing. You were doing something more entertaining.

GK: I was doing something completely different. Yeah. I would jump out of that radio like a crazy man. If you were going down the dial and you heard me, you’d say “What is that? Who is that guy?” A lot of energy. Talking in rhymes. Zeroing in and relating to the city. Playing those requests for people and mentioning they’re on the air and all that jazz.

Anyway, I moved over to WMC and I worked there for about a year and the general manager who hired me left and I knew when he left, I was in trouble because he was the guy who brought me over there. Well, shortly after he left, they called me in. I’ll never forget the guy. He said, “George, we don’t think rock ‘n’ roll’s going to last. It’s a passing fad. It’s like calypso, the tango and the mambo. It’s just a fad. We’re discontinuing rock ‘n’ roll here and you got to go. We’re really sorry.”

Well, Elvis had already hit by that time. I’m kind of jumping ahead. Let me go back when I’m in Osceola. Did I tell you that story when I was in Osceola and what happened with Elvis? It’s kind of interesting. I’m in Osceola and I don’t even have a car. My family didn’t have a lot of money when I was coming up so I didn’t have a car anyway. And I would ride the bus to Osceola and hitchhike home on the weekends. You’ve got to want it bad to be in radio. You’ve got to have that desire to be a lawyer, a doctor, a baseball player, whatever. You’ve got to have that drive, man, or you’re not going to make it. And I had that drive. I had that determination, but I wanted to get my degree too.

So anyway, I’m in Osceola and I came home. I crossed the bridge and stopped by the studio in downtown Memphis to see Dewey. He called me in the studio and he wanted me to hear a record. He put the record on and he held his hand over the turntable so that I couldn’t see who was singing. He said, “Who is that, GK?” I said, “Dewey, hell, I don’t know who it is.” He said, “Well, you went to school with him.” I said, “Well, it’s got to be Elvis Presley. He was the only guy who could sing.” He used to play his guitar and sing in school. So I said, “You mean Elvis has a record out?” He said, “Yeah, Sam Phillips brought me the demo last night. Man, I played it seven times. He’s got a smash hit.” The song was That’s All Right. I said, “No joke. Man, that’s great because Elvis is a great guy.” I always liked Elvis in school. I thought, man, that is fantastic. That’s awesome. Because, Joe, back in those days, to have a record out was a big deal. It was huge. You had big stars with records out. Little guys didn’t have records out. So he gave me a copy and I took it back to Osceola. And I told every jock at the station, “Hey, man, how about helping my buddy and play his record.”

So, anyway, I finished up in Osceola and came back to Memphis. By this time, Elvis has about his second or third record out. I’m at KWAM. Then I go to WMC. While I’m at WMC, Sam sells Elvis to RCA. Elvis comes with Heartbreak Hotel and I Was the One on the flipside. That was his first RCA record.

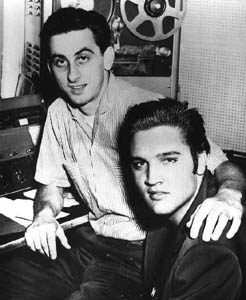

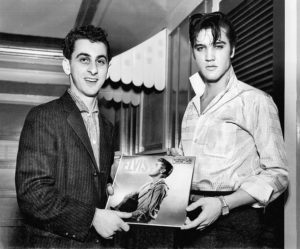

JP: Where was this photo of you and Elvis taken?

JP: Where was this photo of you and Elvis taken?

GK: That was at WMC. Elvis stopped by to see me. He just made the movie Love Me Tender and he stopped by to see me that day. We took that picture and I interviewed him on the air. We shot some video and stuff like that. And then, it was shortly thereafter, I’d say six month after that picture was made, Elvis – occasionally he’d come see me. It was really neat for me to have him come up to the station. The only guys he was going to see were Dewey Phillips and me. Dewey, of course, played Elvis’ first record.

So they told me that rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t going to last and they had to let me go. So I went up to Dewey’s and hung out one night and I bump into Elvis. He said, “Man, what’s going on?” I said, “Elvis, I just got fired.” He said, “What! You were red hot. How could you get fired?” I said, “Elvis, they said rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t going to last.” He kind of laughed and he said, “Well, you’re going with me.” I said, “Where am I going?” He said, “I’m hiring you. We’re going on a big northwest tour. We’re going play Chicago, Detroit, St. Louis. I’m going to play the biggest cities I’ve ever played. Then we’re going on to Hollywood to make the movie Jailhouse Rock. Then we’re going to come back on another tour going through the Great Northwest into Canada.” I said, “Oh, man, Elvis! Fantastic!” Because I was single. I was out of work. And to travel with him, Joe, at that time was a big deal. I never used Elvis, but I knew that he couldn’t hurt me. Now how could it hurt you traveling with the biggest star in the world? I could always go back to radio, but I couldn’t always travel with Elvis Presley.

So I traveled with him for a year. We go out to Hollywood and make the movie Jailhouse Rock. Man, my eyes were about that big. I’d been around a little bit of radio and TV. Being around the real deal. Joe, back in those days, being a movie star was a big deal. You had like Marlon Brando, John Wayne, Jimmy Dean, and Marilyn Monroe. After that, I became a little bit disenchanted with being a roadie.

So Elvis is going in to make King Creole. He gets drafted. I’m at Graceland. He said, “Look at this, you cats. ‘Greetings. Uncle Sam wants you …’” But he got a deferment to make King Creole. So I said, “Elvis, look man. Gosh, I’ve got a shot to go back into radio. You’re going into the Army. Do you mind if I go back into radio?” He said, “Ah no. I know you love radio. You go back into radio. You’ll always be my friend. You can always be with me when you want, when you’re on vacation, you’re downtown, you can hang with me when you get off the air.” I said, “Oh, man. That’s great, Elvis.”

So he made King Creole. So what I did was on the weekends I’d go down to New Orleans. Or I’d take a few days off while he’s filming King Creole and I’m with him down there. He goes to Germany. I go back full time on the radio. Then I start happening pretty big – again. I worked my way all the way back up because I was real hot at one time, then I went down, and then when he went into the Army, I went back to a smaller station in Millington, which is a suburb of Memphis. Worked my way back to Memphis and started at the bottom of the ladder and worked my way back up. So then he’s in Germany and I’m in radio and then I started getting pretty hot again and then I got a TV show.

JP: What was the TV show?

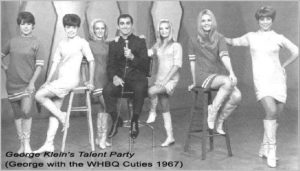

GK: It was every Saturday at 5:00pm on Channel 13 in Memphis, WHBQ Television. It was called George Klein’s Talent Party. It was like The Tonight Show. I sat at a desk with a few chairs for guests. But then I had a lot of musical acts on my show, a lot of music because what happened, Joe, when I took over the show, integration was coming in. Wink Martindale had the show for two years, another guy had it for one year, and then another guy for the next year, and I took the show when the show was on a down side. A lot of acts would come on and lip sinc their records. I took the show over and it was a mish mash. To be quite frank, I started programming the show and helped producing it, and I said with Stax Records happening, with American Records happening, Sun Records still happening, and Hi Records happening with Al Green and everything, we can get all this talent. And I said I’m going to get six girl dancers because there used to be The Shindig Show and it had six girl dancers. So anyway, I put six girl dancers on there and I really made a big-time show out of it. I had interviews, I’d call a star on the show each week, we had a big production number, and then the girls would do a dance number to a hot record.

JP: How long did the show run?

GK: Twelve years. I was on Memphis television for twelve years. I’m not bragging, but television is powerful. Radio was strong, but television, back in those days, was only three or four stations and I was on every Saturday at 5:00pm for twelve years. I had an hour primetime and the show caught fire. Man, we just got red hot. Music started really happening around Memphis and I was having all these stars on my show and I was doing all the right things. The show was just clicking, man. So I got really red hot and did the show for twelve years, but nothing lasts forever. It eventually went off the air.

JP: Were you still doing radio at the same time as the television show?

GK: Yeah, at the same time. I was still at WHBQ Radio and the show got hot and then eventually went off the air.

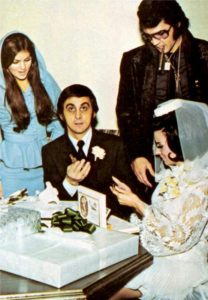

George Klein with Cybill Shepherd “Miss Teenage Memphis”:

JP: You went back to WHBQ?

GK: Yeah, I went back. Oh, I skipped that. When I left WMC and then Elvis went into the Army, I went to the smaller station, and then WHBQ hired me back to do an all-night radio show. From that all-night radio show, I worked my way back up to from nine to midnight, to six to nine, and then went to three to six in the afternoon. And then when I got hot in the afternoon is when they gave me the TV show. It just all coincided. You got to have that radio show for that base audience and then the TV show is like the icing on the cake. And then if you know what you’re doing with TV, then you’re really – and I knew what I was doing – I had a real good director, but I was up on music and had a lot of connections in the music business so I got a lot of people to come on the show. We did pretty good. So I did that show for twelve years and then the show ended, then I went just straight radio. Then FM Radio started coming in at about that time in the early seventies. So I left WHBQ, I think, in about ’78 or ’79, and went to another station.

JP: The radio shows that you went back to, did they focus on rock ‘n’ roll?

GK: Yeah, they were more or less what you would call top forty.

JP: That’s one thing that fascinates me about your career. The fact that your were there from Day 1 when rock ‘n’ roll was starting and through your career, you were in touch with the changes and developments that were going on with rock ‘n’ roll.

GK: Yeah.

JP: Now you do The Original Elvis Hour radio show. Is that the only radio show that you are doing now?

GK: Yes. That the only full time thing that I do. It’s been on Memphis radio for about twenty-three years.

JP: As you are going through all this and seeing everything that was going on with rock ‘n’ roll, were there certain talents that when you first became aware of them, you realized that something exciting was happening. To me, Elvis and the Beatles seemed to create that excitement more than any other individual or group has –

GK: That’s true, yeah.

JP: But apart from them, were there times when you would see certain talents like Otis Reddin at Stax Records or somebody like that and thought this is going to be good?

GK: You mean when a new talent came on the scene? Yeah, that’s true. I knew Jerry Lee Lewis was going to be good. You had to be stupid not to know that. I knew that Johnny Cash was going to be different. Something special because he had a different style. I’m talking about Memphis people. Otis Redding, I knew he was going to be great the first time I heard him. I knew Sam and Dave were too. I knew also Al Green at Hi Records was. Memphis was starting to happen real big.

I don’t mean to brag, but if you have any intuition about you, if you’re really into it, and have any talent to hear a good sound, then you can recognize it. I can’t play an instrument, but I do have a pretty good music and rock ‘n’ roll ear. There were a lot of guys that came on the scene that you could tell were really good. Jerry Lee Lewis mainly. Carl Perkins was pretty good. You knew that he had a different sound and that he was a pretty good Rockabilly guy. Another one that came on the scene that was really great was Charlie Rich. I walked in one day when they were cutting Charlie on his first session. I thought, Jesus, who is that guy? He was the total package. Good-looking guy. Tall. Handsome. Could sing and play the piano. They said that’s Charlie Rich, a new act a Sun Records. I said, oh wow, he’s going to make it. Of course, he did make it. People like that. Now I’m talking about Memphis people and Memphis-connected people.

JP: How about otherwise?

GK: Otherwise, when you heard them on – you know, a lot of the black acts were already there like Jackie Wilson, Sam Cooke, Little Richard, Fats Domino, and Chuck Berry. They were already happening when I was a jock. But new ones that came on the scene –

JP: Like Stevie Wonder?

GK: Oh yeah. Stevie Wonder. A prime example. When heard him, I thought, geez, what a great talent. And also Smokey Robinson.

JP: What about Michael Jackson for that matter?

GK: Yeah, when Michael came on – the Jackson Five – you can say what you want to, and the sad part about – with you being a lawyer – the sad part about his whole situation today is that he’s a great talent. I don’t like the way his private life is, but his professional life as an entertainer, the guy was really good.

JP: On the flipside of that, have there been moments when you thought there was nothing going on in music? No one new and exciting is coming along?

GK: That kind of, sort of happened when Elvis went in the Army. There was a dead zone – I guess you could say like for a cell phone. When Elvis went in the Army, you had these guys who came along who weren’t talented like Fabian or Frankie Avalon and, to a degree, Ricky Nelson. But Ricky developed a style – and I knew Ricky and he was a great guy. Ricky knew that he was not an Elvis singer or a Jerry Lee Lewis, but he developed that low key style when he hit those high notes and he couldn’t bend notes and all that, but he had something. He had a sound. But there was a time element there, I guess when Elvis went in the Army from ’58 to ’60 that you didn’t know where it was going to go. And we got a little nervous because we thought maybe that was it. That was the end. It was just going to fade away. But then what happened was a couple of guys jumped in there and got hot like Tommy Sands and Ricky started getting hot.

JP: What about when the Beatles arrived in the U.S. in ’64? Was that an exciting time for you when you heard them?

GK: For me, it was Elvis all over again. I could see it was an Elvis thing all over again. At first, you thought the Beatles were a flash in the pan because, actually, if you look at it, Joe, some of their early stuff was pure bubble gum – I Want To Hold Your Hand, Love Me Do. But then, you started saying, well, wait a minute, these guys are talented. They may not be great singers, but together they’re good. Very, very good. And individually, McCartney and Lennon were genius songwriters. I heard Yesterday on the air yesterday. God, it sounded great. So, anyway, when the Beatles started happening, there was a little bit of me that said, “Wait a minute. Elvis is my man. I don’t like the Beatles.” But I wasn’t stupid enough to not like the Beatles. I had to be open-minded and I had to say, hey, you know, these are new guys and they’re just out there trying like Elvis tried. I can’t be mad at them because of that. And I started playing them like everybody else. But I really wasn’t happy with the British sound. I was more or less a Memphis sound guy or a Motown sound guy.

JP: What was your reaction to Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys?

GK: Well, I kind of liked the Beach Boys because they were like a white rhythm and blues group. Actually, they were like a lot of Chuck Berry stuff if you listen to them real closely. Early Beach Boys stuff reminds you of an updated Chuck Berry thing. And they were pretty good especially Good Vibrations and Pet Sounds. Like I remember McCartney saying he thought Pet Sounds was one of the best albums he ever heard. And I used to MC the Beach Boys’ concerts in Memphis. They’d come through and I’d be the master of ceremonies. And I became real close to Carl Wilson and to Mike Love. They were good.

JP: I want to ask you about your annual event, the Christmas charity show. How it got started and what it has become today.

GK: Okay, what happened, Joe, was forty years ago, I was on the air and a guy from the local newspaper called me, he said, “George, we have a fundraiser at Christmas time. The Commercial Appeal has a fund called the Mile of Dimes and they give needy people big baskets of food and the afternoon newspaper, The Press-Scimitar, has one called Good Fellows and they buy needy families clothing and toys. And the wrestling matches in downtown Memphis every year at Christmas time have a segment when they take up a collection and donate to these funds. They said, “We want to do something different. We want you to produce a music show right in the middle of the wrestling matches. In other words, we’ll take the ring, the wrestlers will take a 45-minute break, you come on with some acts and then we’ll take up money and that will supplement the intake the funds for the charity.” I said okay. So I produced it and I had Charlie Rich, the Bill Black Combo, Ace Canon, and a girl named Anita Wood who was dating Elvis. It did really well.

So after the show was over and it was a success, the guy said “Look, next year why don’t you do your own thing. Let’s break way from the wrestling matches and we’ll let you produce your own show.” So I went to the National Guard Armory which is where you always had dances and I had the George Klein Christmas Charity Show by myself and it took off like a gem. It was an immediate success. It had local groups. Nothing but local groups and man, kids were packed in there. So we outgrew that and we moved down the road to the fair grounds here in Memphis. There was another building called the Youth Center which was about five times bigger. So we had it there for years. Then mixed drinks came in here in Memphis. I guess that was ’68 or ’69. So the kids were starting to grow up who had been with me. They could get into nightclubs. So we switched it to nightclubs and then to hotel ballrooms, etc., etc. And we did it and it just became a tradition and it had much credibility. We raised a lot of money for the charity. This past year was the fortieth year. This was our grand finale.

JP: What charities were the funds going to?

GK: What happened was The Commercial Appeal dropped their Mile of Dimes fund and The Press-Scimitar went out of business so my committee got together and we decided on three charities. It was Make A Wish, the Memphis Food Bank, and the Memphis Interfaith Association, which bought food and clothing. Then we had a rainy day fund. We put money in the treasury every year we took a little back and put away for a rainy day. And we had some rainy days. We had snowstorms, ice storms. And so we went back and dipped into our treasury and still made almost the same amount of donations at Christmas. One year we had a tremendous snowstorm and maybe a hundred people showed up. So that fund started accumulating. So my committee said, “Look George, why don’t we do this. Let’s shoot for forty years. If we reach forty years, we’ll have a grand finale show and we’ll take the rainy day fund and establish a scholarship at the University of Memphis in your name in the broadcasting department. We accumulated $50,000. It’s called the George Klein Broadcasting Scholarship supplemented by the George Klein Christmas Charityship. So now, next year, if you’re a student at the University of Memphis in broadcasting and you’re having a rough time and you want to apply for aid, then you go in and see them and they check you out and if you’ve qualified, you get part of my scholarship. The scholarship perpetuates itself because it draws interests.

JP: So this was the last Christmas show?

GK: What happened, Joe, is I’m sixty-seven years old and it’s just so hard to do the show. Believe you me it’s a big production and I don’t take it lightly. I mean, I start in October, November, and December working on the show and I make the phone calls and I get the acts and we had an auction in between. While the band was setting up, we auctioned sports memorabilia and other items. All that money went to charity. I mean, I had a committee, but still, everything comes through me and I worry a lot. So I said I can’t do it anymore. It’s tremendous stress. This was our grand finale.

JP: Where was it held?

GK: This year it was at the Gibson Guitar lounge. We had Jerry Lee Lewis, Sam the Sham, Ronnie McDowell, the Hombres, the Memphis Horns, and it was really a good show. Jerry Lee showed up an hour early – it’s the twelfth time he’d done the show for me. He’s got a great charitable heart.

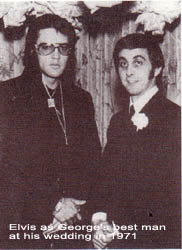

JP: Let me ask you a few questions about Elvis. You guys went back all the way to the eighth grade?

JP: Let me ask you a few questions about Elvis. You guys went back all the way to the eighth grade?

GK: Eighth grade, 1948.

JP: You first met in music class?

GK. Yeah.

JP: In past interviews, you’ve told the story about Elvis showing up in class one day with a guitar and sang and played the guitar and that was one of the first impressions he made on you.

GK: We were in eighth grade music class and we had a real tough teacher. She was really tough. Nobody clowned around in her class. Christmas time was approaching and she said, “Okay class. Next week, instead studying about Brahms, Bach, and Beethoven and musical charts, we’re going to do Christmas carols.” And Elvis raised his hand. He was on the left-hand side of the room. I was on the right side. I can still see him over there. She said, “Yes, Elvis?” He said, “Can I bring my guitar to school and sing?” She made a few snickers and said, “Yeah!” Because nobody could do that in eighth grade.

So he shows up the next week with his guitar and he gets up and actually sings and plays guitar to two country songs. And man, I said geez! Subconsciously, I must have said, “Man! Golly! That’s cool!” At first there were a still few snickers, but once he started singing, there weren’t any more snickers. It wasn’t cool to do that in 1948. So that was my first introduction to Elvis. And then from that, we had classes all the way through high school together. I became class president. I became editor of the yearbook and editor of the newspaper. And I became friends with Elvis. And I was nice to him and he never forgot that. Some of the guys kidded him about his apparel that he wore to school or his long hair. The fact that he had a guitar. But he was very good-natured and a great sport about it. He didn’t rebel or get mad or anything.

JP: Would you talk about the story when he was trying to get into Sun Records and they wanted to know what his act was like?

GK: She said, “Who do you sound like?” And he said, “I don’t sound like anybody.” It was Marion Keisker who was the secretary in the outer office when you walked in and you put down your four dollars to make a record. And then you get in line like a cattle call.

JP: It seems like these early stories of him showed this confidence he had in himself and that he had a plan. That he knew how to do what he wanted to do and he was going to do it.

JP: It seems like these early stories of him showed this confidence he had in himself and that he had a plan. That he knew how to do what he wanted to do and he was going to do it.

GK: That’s right. That’s exactly right. Joe, actually, many, many year later – I wish I had asked Elvis about this, but I kind of figured it out and so did Sam Phillips and everybody else. That was his way of auditioning when he went in to make that record. He was hoping that the people in the control room would hear something and maybe sign him to a contract. But he didn’t want to just walk in and be brash, “I want to audition and I’m a great singer.” He didn’t want to do that. This was his nice way of auditioning hoping they would hear something and they did. And Sam told Marion, “Write this guys name down. This guy’s different.” And six months later, Sam got a song and called him.

JP: You knew Elvis before he was a superstar. When he was just Elvis Presley from Memphis. When there was no guarantee that he would become a star.

GK: What he did was he listened to other entertainers. He listened to the radio a whole lot. He listened to the R&B stations, the country stations, the pop stations. He liked all types of music. He listened to gospel a lot. He’d go up and down the dial listening. He absorbed what they were doing. Then he would go home and he wasn’t with a band. See, the cool way to do it is you get with a band and you rehearse in your garage. You play a high school hop. You play a fraternity party and maybe you get a gig at a country club. But it was just him on his bed with his guitar in his room to cutting a record. He short cutted all that stuff. But he also told me – he did tell me this – that he went to the movie theater and he loved movies. He’d make mental notes. He’d watch and he told me once that Clark Gable didn’t wear a T-shirt. Clark Gable left his shirt unbuttoned for some reason and it would show part of his chest. He picked that up and he thought that was cool. And he noticed that Jimmy Dean would turn the collar up on his jacket in Rebel Without A Cause. And he noticed that Tony Curtis and Brando and all those guys never smiled. If you look at his early, early publicity pictures, he’s not smiling. He said that he thought that the guys that smiled and were blonde-headed had a shorter time in Hollywood than the guys who didn’t smile and were dark-headed. Pretty interesting.

JP: I wish there was more footage of Elvis in the recording studio.

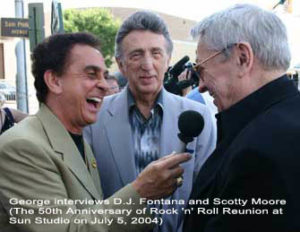

GK: He was learning and absorbing. In his own way, like the way the Beatles did with George Martin. Elvis did the same thing. They didn’t know musical terminology. They would tell George Martin, “We want the drummer to go ba-da-bu-dump-BOOM.” Lennon or McCartney sound out the guitar sound they wanted and Martin would translate that into musical terms and produce what they wanted. Elvis was the same way. He’d go to DJ Fontana on drums and say, “DJ, you give me this lick ba-da-boom-boom-BOOM.” DJ would go, “You mean like this?” “Yeah! That’s cool! And if you want to add to it, that’s okay.” And then he’d tell Scotty Moore on guitar, “Why don’t you do a lick like this?” But he would do it in a real nice way. He wouldn’t try to tell him how to play. “Give me like a – remember that old blues lick that such-in-such used. Give me that lick.” And then he would tell Bill Black, “Give me that heavy bass sound.” In the early years – because I was there – he helped produce a lot of his sessions.

JP: It had to be interesting to watch what he was thinking in making these records.

GK: It was amazing. Now everybody else had carte blanche to throw something in. They’d say, “Elvis, what do think about this?” “Well, let me hear it. Oh, yeah! Use that!” He was open to all ideas.

JP: What was the inspiration in the creativity in his performances?

GK: He felt that you had to give a show along with singing. He said that if you just stood up there and just sang with your guitar, it wouldn’t work. He noticed that when he’d travel early on with those country acts, they were just kind of bland. They’d come out and just sing their songs and that was it. He picked up the entertainment part from black entertainers. He thought Jackie Wilson was the greatest thing he’d ever seen. He thought James Brown was great. He felt that those acts especially the groups back in those days, those acts like the Drifters, the Clovers, and the Platters and they’d come out and do all these fancy moves and later on the Temptations and all those guys did it too. But those guys did it first. Elvis noticed that when they’d move, the audience went nuts in addition to their singing. He noticed when the ones that came out and just stood there, they didn’t get a great reaction, even though they were good talents. But he noticed the ones like Jackie and James and the other ones I mentioned moved around. He felt you had to give a show in addition to singing.

JP: We don’t have to talk about this if it’s too personal, but do you remember how you received the news that Elvis had died?

GK: Oh, that’s okay. At the time I was freelancing around Memphis and I was consulting a theme park in Memphis called Libertyland, a small Disneyland thing here. And I get a call from the radio station, WHBQ, and a guy named Stu Rob, the morning guy, he said, “GK, there a rumor that Elvis passed away.” I said, “Ah, Stu, come on. That’s bullcrap. We went through that a couple of months ago when Elvis was in the hospital and we hear it all the time.” He said, “Well man, can you check it out?” So I hung the phone up. And as soon as I did, the next phone call came in. They said, “Mr. Klein, Line 2.” I pick it up, they said, “George, this is such and such radio station. We got a bulletin across the wire that Elvis passed away. Can you check it out because you’re the only guy we know?” I thought, ah man. About the fourth call was from CBS and they said, “Mr. Klein, this is CBS.” I knew a guy there and I said, “Let me check it out and I’ll get back to you.” Well, I hung up the phone. I called Graceland. Sandy Miller answered the phone. She was Vernon Presley’s girlfriend at the time. I said, “George Klein.” She said, “Yeah. Before you say anything, George, it’s true. You need to get out here as fast as you can.” I was thinking, man, I was hoping it was mistake, you know, that he was okay, that he was going to pull out or something or this or that.

JP: When did you talk to him last?

GK: About three days before he died. So I jumped in my car and drove as fast as I could to Graceland. When I got there, I went into the house and there was turmoil. People were crying and beside themselves. Mr. Presley was really broken up bad. And then I started crying because I felt the emotion. It was just really a bad situation. I think everybody in my generation knows where they were when Kennedy died and when Elvis died.

JP: What helped you get through that time?

GK: Boy! that was a rough time. What helped me get through was not concentrating on the fact that he really had died. That maybe concentrating on the fact it was a big production of some sort.

JP: Like he was just somewhere else?

GK: Yeah, I tried to psychologically sike myself out that I couldn’t think about him actually dying. If I did, it would be bad. So I tried to not think about that until – and the hardest part, I think, was when they brought him up to Graceland in the casket and I had to go look at him. I’m Jewish and in the Jewish religion, they don’t have open casket, but I went up there and I don’t like open caskets, but I went up there and I think I lost it. That was really the tough part. Then after that, I just tried to stay away from the casket. I wouldn’t go back up there. I think I went up there with James Brown when he came to pay his respects. But it was tough. You know, my mother was the toughest loss, but she was eighty something and we knew she was sick. But Elvis was just forty-two and in the prime of his life, a good friend, and he had done all these things for me. Boy, it was tough, Joe.

JP: Was one moment of happiness after Elvis had died when you were asked to receive on his behalf his induction into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame?

GK: That was it, yeah. When I accepted his award into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame, that was probably the highlight of my career connected with Elvis that made the loss a lot easier.

JP: It was Priscilla Presley and the CEO of Graceland who asked you to do this?

JP: It was Priscilla Presley and the CEO of Graceland who asked you to do this?

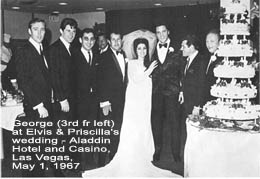

GK: Yeah, it was Priscilla through Jack Soden who was the CEO. Lisa Marie was still as little girl at the time. This was the first induction of the hall of fame. I went up to the Waldorf and Elvis was the last one inducted and I had to sit out there for the whole induction until they got to Elvis. They did like an Academy Award thing. Another famous singer would induct you. I think Billy Joel maybe did Fats Domino and Keith Richards did Jerry Lee Lewis. But when I went up to get Elvis’ award, they did a montage of him singing on the screen. When I get up there, it’s John Lennon’s sons, Sean and Julian, they were both up there. They presented the award. And Julian had on that Elvis button that John Lennon used to wear. Then I made my speech and I would play it to those two. I would say, “And as John Lennon said, ‘There was nothing until Elvis.’” They nodded yes. So I did my speech and got the award and that was the end of it. Then that’s when they had that famous jam session. Then I hung out with Jerry Lee and Keith Richards that night. It was a great memory for me.

JP: The other John Lennon quote about Elvis was “If there was no Elvis, there wouldn’t have been the Beatles.”

GK: Yeah, yeah. There may have been another disk jockey, but I’m one of the few who ever introduced Elvis Presley and the Beatles. I introduced Elvis on stage on the back of a flatbed truck when he was just starting out in Memphis at a shopping center. And then the Beatles came through to play Memphis for the first time. They did two shows, an afternoon show and a night show. I did the afternoon show because I had my television show and I couldn’t do the night show. That was just after John made that statement, “We’re bigger than Jesus Christ.” So I never will forget. They were real nervous about playing Memphis because was one of the first stops on the tour.

JP: Were you interacting with them much?

GK: What happened was, I went to the press conference. I’d already seen them in Atlanta. I went to Atlanta and saw them while I was filming some stuff for my TV show. But then when they played Memphis, I was told by somebody, “Can you please give them a big introduction because they’re really nervous?” So I did and I never will forget that when I came off, Lennon stopped me and said, “Hey man, thanks for that intro.” And he shook hands with me. But when they ran out, it was Bedlam. You know, I liked them and respected them and I was hoping they would make it big. They liked Elvis a lot and they said some nice things about him. They came to meet Elvis. I remember I was at Graceland one time. The phone rang and it was Paul McCartney. They were calling Elvis and to see if they could come see him and he said sure. He had already met them when they came to see him in California.

JP: I want to finish up with your thoughts on the state of rock ‘n’ roll. You’ve mentioned that rap music is suppressing talent.

GK: Yeah.

JP: What are your thoughts on the possibility of rock ‘n’ roll getting back on track? Young kids getting out there, learning to play an instrument and continuing the development of an art form that started with the blues, gospel, country and then rock ‘n’ roll. But now we’re in this period where we’re not seeing the new and exciting talent that once was with the exception of a few artists. Are you hopeful that there will be more new talents that will raise the quality level again?

GK: Yes. I know that there’s got to be some great talent out there that needs a big break. I think the way that it’s going to have to happen is that one of these big rap groups is going to have to say, “Wait a minute,” and is going to have to be really honest and say, “Hey, you know what, there’s probably great singers out there that can’t get a shot because we’re happening so what I’m going to do is establish a label or a production company to help these new talents. Then I’m going to go to P Diddy or one of these hot rappers who say, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, these are the new generation.’” You know who is almost doing it is American Idol. That’s almost doing it. They’re at least giving new talent a shot. They’re not rappers, they’re singers. Those kids are singing and that is a ray of hope there.

JP: In the meantime, what can the generations who enjoyed the music of the fifties, sixties, and seventies do to educate the younger generations so that the Elvises, the Beatles, the James Browns aren’t forgotten?

GK: Try to introduce them to really talented people by buy their CDs. Say, “Look, just listen to this Jackie Wilson guy sing. Or listen to this Clyde McPhatter guy sing with the Drifters. Or listen to Tony Williams with the Platters sing. Or listen to Tom Jones or listen to Roy Hamilton sing. Or listen to the feeling of James Brown on this record. Not a great voice, but a great awesome feeling. Listen to Roy Orbison. You’ve got to get them listening to them because a lot of times I will ask young people who walk up me and say, “Did you really know Elvis. I’m a big Elvis fan.” I’ll say, “How can you be an Elvis fan? You’re sixteen-years old.” And invariably they say, “My parents were big Elvis fans and they had some of the records and CDs around the house and I listened to them. Then they got me to watch a couple of his movies. And I’m not blind and I’m not deaf. The guy was really talented and I really like him.”

I think Elvis, even though he’s has been dead twenty-six, is a ray of hope. But if you can get these young people to listen or if these rappers will endorse – if they’ll get on stage, “Okay now, we’re great, we’re happening, baby, but where it came from was Jackie Wilson, James Brown, the Midnights, and the Clovers! You guys go out there to an old record shop and pick up their records! Listen to these guys, man, they’re cool! We picked up from them! Y’all can pick up from them!” Somebody’s got step out there and lead the way.

JP: Well, it’s good to hear someone like you have an optimistic attitude.

GK: Oh, it’s going to come around. Joe, see, actually music went in ten-year cycles. It was Elvis in ’54, the Beatles in ’64. It was disco in ’74, and rap in ’84 – and well, since ’94, I don’t know what it is. Now some of these grunge acts came out of Seattle, but I haven’t heard a great singer out of those kids. I haven’t heard an Elvis, a Tom Jones, an Engelburt, or Jackie Wilson. Did I tell you what a guy explain to me because I couldn’t understand how those acts were happening. I said to a producer here in Memphis, “Man, those kids can’t sing. They have no range to the voice. They don’t bend notes. They don’t have any inflection. They just get up there and sing and play real loud and they can’t play music. How are they happening?” He said, “George, out of all that junk, on top of all that junk, there’s a hit song and the hit song pulls it through.” If you’ve got a real good song, but you can barely sing, the hit song is going to pull it through if it’s got a message. That’s how they’re doing it until somebody bounces through. And maybe these acts from American Idol. The only problem with those acts is that it turns into a popularity contest as opposed to a talent show.