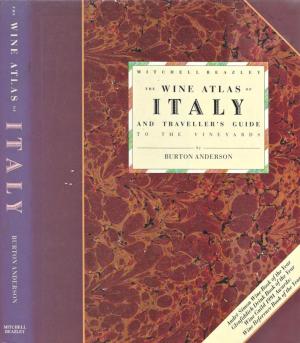

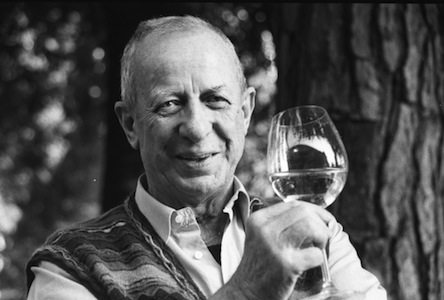

Burton Anderson has been called by many, including other world renowned wine experts and journalists, the leading authority on Italian wines. As an established journalist and editor from the Midwest living in Italy for more than four decades, he wrote many important articles and groundbreaking in-depth books on Italian wine. When the Italian wine industry was experiencing a renaissance which was revving up in the 1970s, Burton was right there to write about it and provide a road map for his readers in understanding the vast and confusing subject of Italian wine. No one had achieved this before him. He received critical acclaim for his work and quickly established himself as the most informed writer on Italian wine. The New York Times called his first book, Vino: The Wines & Winemakers of Italy (1980), “the standard reference, in Italian as well as English.” In 1990, his masterpiece, The Wine Atlas of Italy and Traveller’s Guide to the Vineyards, was published. Among other prestigious awards, he received the James Beard Award for Writing on Wine in 1990. In 1994, he completed and published Treasures of the Italian Table. The following year, this book earned him another James Beard Award this time for Writing on Food.

I don’t remember when I first heard about Burton Anderson. But, I do recall that I was still living in Washington, D.C., when I bought a copy of The Wine Atlas of Italy. It was a helpful guide to have with me when I visited the wine regions of Italy while I lived there for seven years. Just a few months after I earned my WSET Diploma in London and a few weeks before I moved back to the United States, I visited him where he lived at the time in Tuscany. I never published this interview because I moved to New York at the end of 2007 to work in the wine industry. So I put my website aside. But I’ve held onto the tapes of this interview. Now, twelve years later, I am publishing my two-hour interview with him in three parts for the first time. In this first installment, we discussed his background, career, and writings. In the second installment, we discussed in-depth his thoughts on Italian wine. In the last installment, we finish up talking about Italian wine history and Italian cuisine. Here is Part One:

* * * * * * * *

October 18, 2007 – Loro Ciuffenna, Italy

Joe Pascale: It’s my opinion and many would agree that you are the leading expert and scholar on Italian wines. Other renowned wine experts in their writings often defer to you when discussing Italian wines. Yet for someone of your stature, there is little information about your background.

Burton Anderson: I first came to Europe in the 1960s to work for an American newspaper in Rome called The Rome Daily American and I stayed there off and on between 1962 and 1968. That’s where I got interested in wine and food. At that time, eating in Rome was a real joy because it cost nothing and the food was really good. It wasn’t as touristy as it is now. The wines were not always so good, but I started going out and looking for things other than the house wine. That took me to Umbria, Tuscany, and Piedmont. It was an interest that developed while I worked for this newspaper.

Then in 1968 I got a job as the news editor of the International Herald Tribune in Paris. In terms of a career, it was a great move, but it took me away from Italy. Even though I adore French wines, French foods, and all that good style, I felt homesick for Italy. I lived just outside of Paris for nine years, but in the meantime, I bought a house here in Cortona. Every free moment I had — I had been working nights and getting a lot of extra time off — I was spending maybe three to four months a year down here doing research in wine and remodeling this house.

Finally in 1977, I said I’m going back to Italy and I quit my job at the Herald Tribune, packed up the family in the car, we drove down, and that was it. I wrote the book Vino: The Wines & Winemakers of Italy which came out in 1980, and I followed that up with the Pocket Guide to Italian Wines in 1982 which was first published by Mitchell Beazley in London and since then there have been many editions of it in many languages.

JP: Where are you from originally?

BA: Minnesota.

JP: Did your professional career always involve wine?

BA: I was a journalist. I worked for newspapers. I was basically an editor, but I actually prefer writing. I was the news editor for both the Rome Daily American and Herald Tribune. But at a certain point editing at night gets kind of boring and I always preferred writing.

I just got this thing about Italian wine and started studying it. Because there was nothing of any particular value on the subject in English, I sort of filled a void with Vino. I started working for an Italian wine magazine called Civiltà del Bere, the English version was called Italian Wines & Spirits. This was something to keep me going while I was writing the book. Vino came out in 1980 and it at least had critical success. It surprised a lot of people because Italian wines were so lowly regarded at that time that it was kind of a revelation to a lot of people. It did establish a reputation for me. After that I did a lot of article writing for various publications. I wrote the Pocket Guide. In 1990, I wrote The Wine Atlas of Italy and Traveller’s Guide to the Vineyards which I consider my major work on Italian wine. But a lot of people prefer Vino because it is more familiar in a way.

JP: The maps in The Wine Atlas of Italy has not been surpassed with their detail.

BA: Unfortunately, it hasn’t because for some of the maps I was able to take from what existed. But for most of the maps, I actually sat down and sketched out and worked with a cartographer in London who put the maps together. I wasn’t entirely satisfied with them because this was pioneering work and they needed to be refined and improved on and expanded and so on. But unfortunately, the publishers just never got around to doing another edition.

JP: It hasn’t been reprinted at all. Are you aware of the value of that book? I’ve seen it being offer for several hundred dollars.

BA: I’ve seen it on a couple of websites up to a thousand dollars. It’s because there are so few copies.

JP: When you moved to Italy in 1962, did you have the intention to stay this long?

BA: No. I liked Rome. Rome at that time was a paradise. Apart from La Dolce Vita and that sort of thing, it was really a great place to live. It was, other than Trastevere, like living in a small town. Everybody knew everybody. Just a great time. I’m sure it’s changed a lot but I haven’t been down there for so long. I stay here and write most of the time.

I really fell in love with Italian wine and food, and I what I realized was you can’t generalize Italian food. Living in France, there is a French cuisine. Of course, there are variations in Provence and Normandy and places like that. But there’s a base in France. There is not in Italian cucina. This is something I’ve tried to emphasize. Also at that time, there was not a national concept of wine. It was very much regional, provincial, and local. This is what always fascinated me about Italy. The fact that you could go ten kilometers down the road and taste different dishes and wines that are from a completely different grape variety. In fact, Vino was kind of a voyage of discovery for me. It involved going around and meeting people and finding out what was going on.

JP: How long did it take you to research and write Vino?

BA: I started working on it in a casual way before I left Paris in 1977. My first intention was to write about northern Italy first and then southern Italy. But then I thought, no wait, southern Italy isn’t important enough as a wine country to do that. Luckily, after it was rejected by at least ten publishers, I sent the first half of it – all of northern Italy – to Little Brown in Boston. The guy in Boston said, this is great but I’ve got to have the whole country and I want it in nine months.

JP: How much did you have done at that time?

BA: At that time, I was starting to work on Lazio, Le Marche, and Abruzzo. I had already done northern Italy. I did all of southern Italy in nine months – killing myself – including Sardinia and Sicily. It involved driving around in my car with a mattress in the back. Incredible enthusiasm that I had in those days helped me get this done.

Also, The Wine Atlas of Italy was a tremendous amount of work. That was a harder book to write because of the maps and the amount of detail that I put into it. The atlases they were putting out were modeled to some extent after Hugh Johnson’s World Atlas of Wine. His, of course, was somewhat more technical in detail. My book required not only getting into my heartfelt feelings about wine, people, and food, but also getting into the technical details on soil and microclimate and this sort of thing. Vino was much more casual – I just skipped over a lot of things. Where with The Wine Atlas of Italy, I was trying to get everything in and I guess you can’t in Italy because there’s always something left to be discovered.

That was a tremendous amount of work and I really did want to wait about three or four years and update it, but it didn’t happen. The publisher, Mitchell Beazley, was simply working on a straight budget consideration and it would have cost so much to produce – the maps especially. And I was saying, look, if I do it again, I want much more money than you gave me the first time. And I want maps that are going to cost more because they have to be better and in more detail. They basically said, you’re beyond our budget.

JP: No other publisher was interested in doing it?

BA: They really couldn’t take it at that time because the maps were all copyrighted by Mitchell Beazley and they weren’t about to give them up. It is too bad. At that point, I really kind of lost interest in continuing to write about wine because after the amount of work I put into that book. And the success it had without actually being a financial success as something that could be revised kind of discouraged me. I wrote a book mainly on food after that, Treasures of the Italian Table. I wrote a lot of articles on wine in the 1990s. At one point, I even wrote for Wine Spectator for a while.

JP: How long did you do that? I can’t see you doing that with your approach to discussing wine so different from Spectator’s.

BA: In fact, I really didn’t like working for the Wine Spectator. I didn’t like Marvin Shanken and his attitude toward advertising. I wrote two years for them and then I said no. After that, I freelanced. That was in the 1980s when they were first starting out.

JP: That was in between Vino and The Wine Atlas?

BA: Yes. And then after Wine Atlas, I was freelancing. A lot of stuff for Decanter, Quarterly Review of Wines, and Wine Today until it folded.

JP: Since the time you began writing about Italian wines, are you surprised that Italian wines have come such a long way in quality and production?

BA: To some extent. I was pretty brash in my early days. I was predicting it. I kept saying it. I lived in France for nine years and I’ve driven all over France. I’ve tasted all the wines from everywhere in France and generally I prefer Italian wines. There’s great Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne – unmatchable wines. But overall, Italy makes better wines – even country wines.

JP: What makes you say such a strong statement?

BA: It wasn’t so much that I disagreed with the wine snob opinion that there’s French wine and that’s it. The English for example: I remember I had a feud going for years with Michael Broadbent on whether Italy could make great white wines. He said, well, there’s maybe a few Barolos, maybe a Brunello that might stand up to France, but otherwise Italy has nothing. I said okay, Michael. He admitted, though, that he had never been to Italy and he did not taste many Italian wines. I developed kind of a partisan approach because I felt that Italy was being slighted by everybody mainly because people were too lazy to get out here, to see what the potential was, and to see what was happening.

Italy was a huge importer of wine to the United States, but Lambrusco accounted for more than 50% of the wine imports into the United States in the late 1970s. Soave was being imported, but Riunite was the big thing, which allowed the Mariani family to start Banfi. So here was also Soave, Bolla, Ridicchio, and Frascati, but nothing of any prestige apart from a few bottles here and there. For instance, the Biondi-Santi Brunellos in 1960s were making an impression because they were so unusual – different say from the great French wines and yet to me they could stand up to them in their own style. But in that time there were only something like seven or eight producers of Brunello and today there’s more than 200.

Not to pat myself on the back, but I did see this coming because I did know while I was going around writing Vino was when I became convinced that Italy could produce not only very good competitively priced wines, but also excellent wines on their own and with the advantages all these native grape varieties which nobody else had. In those days, I think I was the first person to ever write about Sagrantino and the first Sagrantino I tasted was one bottle was good, one bottle was awful. That sort of thing. But I said to the producers that there’s a great potential here. Why don’t you start getting serious about it? Hire a professional enologist.

JP: I think that slight toward Italian wine still exists. While I was pursuing my Diploma at the WSET in London, we spent about two weeks of classroom lectures on French wines and only two days of lectures on Italian wines.

BA: And that’s a big improvement from what it was. I actually gave a lecture to the Institute of Masters of Wine in either 1981 or 1982 right after Vino came out. That was the first time that anyone had ever spoken to the Institute about Italian wine. The only reason that I went was because Serena Sutcliffe MW was interested in Italian wine. And Nicolas Belfrage MW who then ran the educational part of the program was interested. Luckily, there were people like Belfrage who is partisan like me for Italian wine so he made some inroads in England. But it’s true, the English are still a little bit snobby about Italian wine.

Serena Sutcliffe

Nicolas Belfrage

JP: Was there a point that you believe the world finally started to get it that a variety of quality wines were being produced in Italy?

BA: I had the impression that Americans generally were getting interested in the early 1980s. Wine writers, for example, who are opinion leaders. Vino had a big influence on them. People like Bob Finigan who preceded Robert Parker as having the most important newsletter came over and spent a week with me and was very impressed. Hugh Johnson came over and spent a week and actually was trying to get me to work for him in doing the Italian part of his books. He did have a tendency to like them. But before that, they didn’t even want to know about Italian wines. Americans immediately took a liking to Italian wines and saw the potential. It took Hugh three or four years before he started writing about the potential of Italian wines. Michael Broadbent never saw the light.

Jancis Robinson and Oz Clarke were younger than Hugh and Michael so they were much more open to Italian wine. I think their work has been very important for the English-speaking market.

Jancis Robinson

Oz Clarke

JP: Your development as a wine journalist paralleled the time when the importance of the wine journalism profession was developing. Many wine journalists fell into the role of being a wine critic. You, on the other hand, have been more than simply a wine critic. You show that there is more to a wine than just analyzing the wine itself. You show that it’s also important to discuss the background and history of the region, the people who make it, and how it relates to the cuisine and culture. Is that a fair description of how you differ from many other wine writers?

BA: Absolutely. That’s right on the mark. To be honest with you, I easily could have been a part of that type of wine journalism, especially as an Italian wine critic. But it just didn’t appeal to me. I don’t believe in the numbers system. There are arguments on both sides of it, but I am very much on the side of the real wine writer and not the wine rater. A wine writer can be critical without numbers. Sure, there’s a legitimate reason for ratings, but to sit down and write about a wine in absolute point ratings that will absolutely influence the wine market to me is almost corrupt. Even though I think Robert Parker is perfectly honest. I have no reason to think he isn’t. I think the Wine Spectator people are generally honest.

I think ratings have ruined wine writing. The only real wine writers left are mostly the English. I think there are still some in the States. But the people who are making an impact in wine literature – even that is fading since the 1980s and 90s – are raters. Parker has totally dominated. More power to him but what bothers me is that his readers and the wine buying public just watch those numbers. The descriptions are totally unimaginative. They use the same terms over and over again.

My last book on Italian wines was Burton Anderson’s Best Italian Wines which frankly I don’t consider it one of my better works. I did it because people were insisting that I do it. Those descriptions that I gave in the book were to me getting too much of a standard news style wine analysis. And I realized also that there wasn’t really much of a market for the kind of book I’d be writing which could have actually been very critical in general of the trends in not only in winemaking and wine production but also in wine writing, but it would have been sour grapes.

JP: I’ve heard you’ve been working on a novel.

BA: I’ve written a novel. Something called Boccadoro. Just came out. It’s just kind of a joke, nothing serious. Now I’m writing a book about an ancestor of mine – this is also kind of a joke – who was the margrave of Tuscany in the 10th century. His name was Boso and there is so little about this character. His brother was the king of Italy. He was descended from Holy Roman Emperors.

JP: It’s interesting to hear you say that wine literature is going downhill while there has been a continual interest in wine tourism. You would think there would be a continued demand for wine literature.

BA: Well, another facture is that it is so easy to look up information today. Back then a book like Vino was a reference source. Today, even if someone writes a book like that, it’s just going to be to read for fun. Because if you really want information, you are going to go to the internet to look up something.

JP: Were there any Italian language wine writers like Luigi Veronelli doing the same sort of writing you were doing for Italian readers?

BA: He did write a couple of books, but after that, he got mainly into becoming the guru in writing wine publications that weren’t by any means a great piece of literature. They were well done, well researched. He was doing something else. But he was so important. He had – for different reasons – the same kind of power over the Italian wine market and Italian wine production that Parker has had in the States. Veronelli was the wine person here. We knew each other. We kind of had a grudging respect for each other. He wanted me to work for him, but I never did. We got along. I certainly wasn’t a competitor of his in Italy and he wasn’t a competitor of mine outside of Italy.

There’s something about the Italians – it’s changing now – but it’s so easy to buy off somebody here. Even if you are honest, you’re going to be accused of corruption. In fact, I have a reputation as being the only honest person in Italian wine which is a joke. I consider myself more or less honest, but I’ve taken a few trips and freebies. Take Gambero Rosso for example, there are so many stories that have circulated about them. I don’t know a wine producer who has nice word to say about the people who run Gambero Rosso even though they may get a three bicchieri rating.

I’m sure there are some good Italian writers who are writing about wine. I really don’t follow them a closely anymore. Italian writers tend to be good at that sort of writing of describing the wines and the people who make them.

JP: Are you currently writing for any publications?

BA: No, because I’m not really that well informed.

JP: You still make lecture appearances?

BA: Yes, I do probably fifteen to twenty appearances each year mainly in Tuscany. And mainly for tourist groups who come over. People are always fascinated by tasting four or five Tuscan red wines and having me described them. That’s what I think is missing. I very much would have liked to develop that but with the dollar down it’s not going to happen and I’m not good at organizing that sort of thing.

*********

Coming Soon: An Interview with Burton Anderson – Part Two, in which we discuss his views on Italian wine.