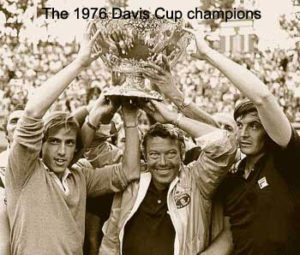

Adriano Panatta was one of the most talented and dynamic tennis players in the history of the game. In the 1970s, the golden era of professional tennis, he was one of the premier players on the professional circuit. He had important wins over all the top players at the time, including Ilie Nastase, Jimmy Connors, Arthur Ashe, and Bjorn Borg. During 1976 when he earned his highest career ranking at No. 4, he became the French Open champion defeating Borg along the way to capturing the title. In fact, he was the only man to defeat Borg when the Swedish Ice Man reigned as the six-time champion at Roland Garros from 1974 to 1981. In the same year, he led Italy to its only Davis Cup title, although he and his teammates took Italy to the finals the three subsequent consecutive years.

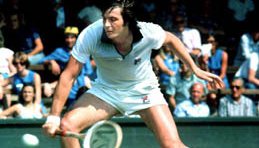

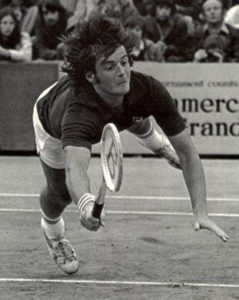

Those who saw him play or played against him were aware of his imposing serve-and-volley style of play that was a lethal combination of power, speed, and touch. One of the few times that Panatta came to the attention to the general American public was when CBS televised his epic five-set loss to Jimmy Connors in the fourth round of the U.S. Open in 1978. Connors won 6-4, 4-6, 6-1, 1-6, 7-5. But both of them were praised for their miraculous level of tennis on that afternoon that caused this match to become one of the most memorable battles in tennis history.

Panatta retired from the professional circuit in 1983. Since then, he has held several positions in the Italian tennis world including, Davis Cup captain, the Italian Tennis Federation national coach, tournament director of the Italian Open, and publisher of his own tennis magazine. But the activity that he has been most passionate about since retirement is competing in offshore speed boat racing. In 2004, his team won the world championship. He also holds two speed world records.

I met with Adriano at his office in Rome on February 9, 2006, to discuss his early development, highlights of his career in the 1970s, his life after retirement, and his opinion on the state of tennis today.

Joe Pascale: Many of us Americans remember you from the 1970s. We saw the excitement that you brought to the game. However, since television coverage of tennis was not as extensive as it is today, there wasn’t much of an opportunity to see you play – unless one was fortunate to see you play live. We didn’t know much about you. What I would like to do is to first talk about your early development as a tennis player, some of the highlights of your career, what you did after you retired from competitive tennis in 1983, and then your opinion on the state of professional tennis today.

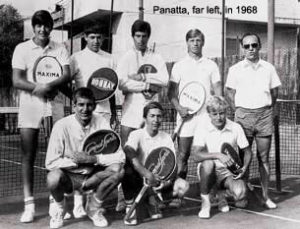

Adriano Panatta: Ok. I started at a very early age because my father was the caretaker of Parioli, the most important tennis club in Rome. I used to watch tennis all the time when I was very little. I started there, but playing just against the wall. Then when I was eight or nine, my father sent me to tennis school. As I grew up, I would win a few tennis tournaments. In Italy, we had a national camp between Naples and Rome. It was a very big national camp. Not only for tennis, but also for track. We all were there for a long time practicing, we were the national junior team for five or six months with my coach Mario Belardinelli who was the most famous tennis coach in Italian tennis history. He coached all the best players at the time. He brought up the new generation of tennis players in Italy. Nicola Pietrangeli, was already established and close to the end of his career. He was seventeen years older than me. Belardinelli developed the new generation of players – myself, Bartutti, Bertolucci, Brunorelli. Then I started to be professional. In 1968, we flew to Australia in the wintertime. This was the first time that we went away from Italy. We spent three or four months. My first big win was Clark Graebner, you remember him?

JP: Yeah, big guy. Glasses.

AP: Superman. Yeah, we called him Clark Kent. I beat him as a junior. Then I started my professional career.

JP: Before we get into your professional career, I’d like to talk about your style of play, which was unique for an Italian player.

AP: Really?

JP: Oh sure. You had a strong serve and volley game which is not a typical style of an Italian player. In such a baseliner environment, how did you develop your attack style?

AP: I’ll tell you how it happened. When I was a junior, I was very little. They used to say, when I was 14 or 15, it is really bad luck that this young kid plays very well, but he does not grow up. So when I was in Australia, the tournaments changed my game completely. I changed physically. Because when I came home, my parents said, “What is going on with you. You grew up. You’ve become a man.” Whatever.

JP: You actually grew taller in those three months?

AP: Yeah, taller and bigger in just three or four months. So I started to play a new game, especially with my serve. For me, it was very natural to serve and volley. Actually, I was really a clay tennis player. My backhand was very steady on the baseline.

JP: Did it also help seeing the Australians play?

AP: Yeah. I think I changed my mentality over there because it was something new. Everybody was there, Laver, Emerson, Rosewall. All the tournaments were there at that time of the year. I understood that if you want to be a successful tennis player, you had to learn to attack.

JP: To win you have to have a level of confidence that you know you can win.

AP: It is definitely something going on inside. You know what’s going on. You see it all the time, for instance, when a college player is on the tour the first time. Many are overwhelmed. He doesn’t know what’s going on. Many things must go together to become a professional tennis player.

JP: I noticed in the early 70s was when you began to have a presence on the tour.

AP: Well, the first big tournament that I won was in 1973. I won the English Open which was on clay. I beat Nastase in the finals.

JP: You also beat him in the first round of the French Open in 1972.

AP: He was number one in the world at that time.

JP: He must have hated you for doing that.

AP: No. He forgave me. We are still very, very good friends. He is a very nice guy. A special guy. A big heart.

JP: Everyone says that he is the nicest guy – off the court.

AP: Yes. This is very true. Also on the court, it was not always bad. When he would get like that, you could sometimes just tell him, Nastase, stop now, okay? He would only really be Nasty when he played someone who didn’t like him. But when he played a friend he’d try to mess with you. You could say, Nasty, will you stop now or do I break your hand? And he would start laughing. A really special guy.

AP: Yes. This is very true. Also on the court, it was not always bad. When he would get like that, you could sometimes just tell him, Nastase, stop now, okay? He would only really be Nasty when he played someone who didn’t like him. But when he played a friend he’d try to mess with you. You could say, Nasty, will you stop now or do I break your hand? And he would start laughing. A really special guy.

JP: In 1974 and 1975 you continued to have important wins.

AP: Yeah. I won in 1974 the Florence Open. Then in 1975 I won the Swedish Open beating Connors in the finals, Ashe in the quarterfinals. A very big tournament for me. A fast court. Indoors. I really liked playing indoors.

JP: By the time 1976 came around you had some wins over the top players. You then went on to win both the Italian Open and the French Open. Was there something different you did that year that helped you win that year?

AP: I think sometimes something magical happens and you don’t know why. You just have it. You say to yourself that you are going to put the ball right where you want it and it happens – all the time. Something that I cannot describe. It just happens. Everything becomes easy. In Rome that year when I won the tournament, in the first round I had 11 match points against me. I won and then I went on to win the tournament. Same thing in the French Open. A tough first round against Pavel Hutka. He had one match point against me. At that time, the Italian Open and French Open were back to back which was very tough. I won the Italian Open on Sunday afternoon and the French Open started on Tuesday. I won the match and then went on to win the tournament.

JP: Along the way you beat Borg in the quarters who beat you the year before. And then you beat Eddie Dibbs and Harold Solomon, two players you never seemed to lose to.

AP: No, I don’t think I did against those two. Against Borg – how many times did he win it around that time, five times in a row?

JP: Six times between 1974 and 1981. He was the two-time defending champion the year when you beat him.

AP: He only lost against me during that period?

JP: Yes, he didn’t play the tournament in 1977.

AP: He didn’t like to play against me even though we are very good friends. But he did beat me here in 1978 in five sets. I liked to play him. His game didn’t bother me on any service.

AP: He didn’t like to play against me even though we are very good friends. But he did beat me here in 1978 in five sets. I liked to play him. His game didn’t bother me on any service.

JP: Your Wimbledon career record was interesting.

AP: It was not a very good record.

JP: Well, I noticed a pattern. You always won your first two matches, except for 1979 when you got to the quarterfinals when you beat Sandy Mayer to get there.

AP: Yeah, I threw away my match in the quarterfinals against Patrick DuPre.

JP: Really? What happened?

AP: Threw it away. It’s the only match in my career that I regret losing. I was very confident at that time. I was playing great tennis, but against DuPre I lost my concentration.

JP: You beat him in the finals to win the Japan Open in 1978.

AP: Yes. At Wimbledon, I won the first set easily and then I was up 4-1 in the second. There were so many times that I had the match over with. I was stupid.

JP: It wasn’t important to you?

AP: No, it was very important to me, but I started to play a bit cocky. I was very sure about my game. But then when you lose your concentration, you get frustrated. I lost the second set. Then I won the third set. Then I lost the fourth set and then the match. That was my year to play well at Wimbledon. I wanted to get to the finals to play against Borg. Even today, Borg says to me, “Adriano, I was sorry for you, but ….”

JP: That was the year that he beat Tanner.

AP: Right.

JP: When you won the French Open, there had to have been a big celebration in Italy. You became a national hero.

AP: Yeah, but also because it was the same year we won the Davis Cup.

JP: The one thing I noticed about your Wimbledon record was that you were consistent. You usually won two matches and then lost in the third. You never lost in the first or second rounds. If anyone wanted to place a bet on you in the first or second round, odds were you’d win.

AP: Ha-ha-ha-ha. This is the first time that I heard this.

JP: What’s funny to me about this photograph (see further down below) is that I never saw you play live, but I saw both Jaime Fillol and Patricio Cornejo play against Stan Smith, Tom Gorman, and Erik van Dillon in the Davis Cup quarterfinals in 1973 in North Little Rock, Arkansas.

AP: Really? Jaime was a very good player.

JP: He was another one you never had a problem to beat.

AP: True.

JP: That had to been a special time for you in 1976.

AP: That was my year.

JP: But that was just the start of the run you led for Italy getting to the finals of Davis Cup.

AP: Four times to the finals. We won the first one when we beat Chile.

JP: The finals in 1979 in San Francisco was a difficult time. Just a few weeks before, you lost your coach Umberto Bergamo.

AP: He was my best friend. It was also impossible to beat the U.S. that year. They had the best team at that time. Before that in 1977 we lost to Australia in Sydney. I lost a five hour match to John Alexander. I broke my racquet when I served for the match. Then we played Czechoslovakia in 1980. That was a big scandal. After that, they changed the rules to put a neutral umpire in the chair.

JP: Regarding Davis Cup, to players like yourself, McEnroe, and others, Davis Cup was important and a duty. If you were asked to play on the team, you played unlike many other players who didn’t want to take the time for it. It was always a high priority to you.

AP: Until the 1980s it was very important to everybody who played Davis Cup. I would say now the value of it has gone down. The professional system is not educational. I think a few values have been lost. Values now are only money, ATP points, and contracts, which are very important, but the value of Davis Cup should be very important also.

JP: Obviously your 1978 U.S. Open five-set loss to Jimmy Connors was a difficult loss. Do you realize that the fact that you lost that match is not important to many Americans? You are still viewed as one of the great champions of the 1970s. For many Americans, that was the only time they saw you play on television. They remember your exciting style of attack tennis.

AP: They tell me that since then whenever there is a rain delay at Flushing Meadows, they play that match on television. Is that true?

JP: That’s true.

AP: Really. I remember one thing about this match. I remember the day after. I arrived in Flushing to go to the players lounge. Inside there is a big blackboard for reserving practice court time. Late in the morning I went there to collect my things and someone had written in big letters “Panatta Ancora!” (Panatta Again!) The guys who were in the lounge all applauded me when they saw me. It was nice.

JP: My coach was in the stadium during that match and he remembered it well. He described your game was similar to Stephan Edberg. Solid groundstrokes and serve. Attack the net. Crisp volleys. And very fast.

AP: I see what you mean. One thing that I remember during that match was that most of the top players, men and women, respected me. I can feel it when I see them today, I don’t know why. I remember during this match against Connors that many of the top players came to watch the match in the stands. I remember Martina, Chris. Men and women players were there. It was a very close match. Very tough. Jimbo was the toughest player to beat. Fought every point. More difficult than Bjorn even though Bjorn was a better player.

JP: Although you had wins over Connors in other tournaments, you still thought Connors was more difficult to beat than Borg?

AP: No, no. I mean Connors was the most difficult player to beat psychologically, especially in Flushing. Borg won more grand slams, but he never won Flushing. The nighttime lights bothered him. Connors loved playing at night in front of the big crowds.

JP: You had a strong doubles careers.

JP: You had a strong doubles careers.

AP: Especially Davis Cup. It was very difficult to beat us in doubles. I didn’t like playing doubles in the tournaments because it was too tough in the grand slams to play both singles and doubles.

JP: It’s even worse now because very few of the top players are playing doubles because of the physical demands on singles.

AP: Doubles now is getting ridiculous.

JP: What do you think about the experiment of shortening the scoring in doubles so that more top players will play?

AP: The top singles players should play doubles. Maybe in a different way.

JP: Why do you feel that way?

AP: Because who cares if Mr. Shmuck is playing doubles!

JP: We call them doubles specialists.

AP: Yeah, but – doubles specialists, my ass. No, they play good doubles, but people don’t come to the tournaments to see doubles specialists. When McEnroe and Fleming used to play, Newcombe and Roche, Okker, Riessen, myself, and others. I mean, it was very interesting. You’d go and watch the doubles. Those were really good tennis matches. Right now, I mean, it’s the Bryan twins against whoever.

JP: Do you think this new format might bring the top players back to doubles?

JP: Do you think this new format might bring the top players back to doubles?

AP: I don’t know. Now it’s difficult to recuperate it.

JP: The state of tennis today. I’ve seen some of your comments. First, how do you feel about the change to more powerful racquets than what you had in the 1970s?

AP: It’s not a game now. You can play some shots that you couldn’t play back then, no way. Especially, when you run down a ball on the defensive, back then all you could do is lob. Now you can hit all different shots. That’s normal these days.

JP: I think that one improvement for everyone is that the tennis shoes have improved.

AP: About the best thing you could say about the shoes back then was that they were very light.

JP: You made the comment that others have made which is that Roger Federer is the only one today playing a true and interesting tennis game. The rest are just pounding from the baseline.

AP: Yes, Roger. Agassi also. He showed a new way to play the game. Both are something special. Sampras was too.

JP: I’ve always liked Sampras’ old school style. Like you guys played. Serve and volley. One-handed backhand.

AP: Yeah, that’s true. Federer when you watch him play, it’s something nice. When I watch tennis on television, I watch Federer. The others I stop watching after five, ten minutes. It’s always the same. There’s no surprise. They play well. They’re very consistent. They’re strong. Please understand I’m not one of those old guys who played tennis, “In my day . . .” I mean I respect them. I just don’t like it very much. Nadal, for example, is a special guy who plays in that style. It’s like in music, the movies, or whatever. It must surprise me. If it doesn’t surprise me, I don’t enjoy it.

JP: I hope that Nadal, because he’s young, learns the things he must develop in order win on other surfaces like grass.

AP: Now it’s easy to win on grass. It’s easier.

JP: Because the grass has changed?

AP: No, because there are no more grass specialists. Bob Hewitt from South Africa was tough. Before, to win on grass was difficult. If you played on grass at that time, to beat Bob Lutz on grass was difficult. On grass, you’d have to play your top game to beat him. Now, the last one who was a grass tennis player was Pat Rafter. Today, if you beat David Nalbandian – a baseliner – on grass, it is considered a good win.

JP: Don’t get me started.

AP: You see.

JP: I saw a remark by Vijay Amritraj and Martina Navratilova that something that has been lost from the 1970s era is that there were more unique styles as well as personalities.

AP: Yeah, the generation was different. The world was different. People’s interests were different. The music was different.

JP: The prize money was different.

AP: The prize money was okay, but everything was different. Now – we come back to the values – the values are different for the younger generation. What kind of values are these? I don’t know.

JP: What are your thoughts on the future of tennis?

AP: We need to make a very important turn in the game. We need someone to come in who can do that. Right now the managers in tennis in ITA, ITF, ATP, WTA, and other tennis associations are all the same. I’m not talking just about Italy, but everywhere I think. Why don’t we have a former tennis champion who can be the chief executive? It’s always somebody from like Pepsi Cola. It’s letting politics take over. In the beginning when the rules for professional tennis were created in the 1970s, the first board was myself, Arthur Ashe, John Newcombe, Bob Lutz and others. When we talked, we knew what was going on and something that we all felt the same on. But now, the ATP director is someone who has no background in the game of tennis. Instead, it is someone who was the head of some big corporation. So what. In skiing, Jean-Claude Killy is involved in the international committees. When you talk about football, Michel Platini is involved. Why not in tennis?

JP: Since you retired from tennis in 1983, what have you been doing?

AP: When I stopped, I was working for the Italian Tennis Federation. I was Davis Cup captain for about 15 years. Then I was the Italian national coach. Then I was tournament director of the Italian Open for three years. I’ve had my own office to manage things including my tennis magazine. And I race offshore boats.

AP: When I stopped, I was working for the Italian Tennis Federation. I was Davis Cup captain for about 15 years. Then I was the Italian national coach. Then I was tournament director of the Italian Open for three years. I’ve had my own office to manage things including my tennis magazine. And I race offshore boats.

JP: When did you start the boat racing?

AP: After I retired from professional tennis, I started to race offshore.

JP: Where did that interest come from?

AP: Because I like very much motor sports in general, especially on the sea because my family house is in Viareggio, which is the capital of offshore in the world. My wife is from Tuscany and my two sons and daughter all like Tuscany. They’re all grown up now.

JP: You won the championship in 2004.

AP: Yes, we won the championship in 2004. Before that, I won a few European races. I broke a couple of speed records.

JP: You are the throttle man, the guy in the middle is the pilot, and the third guy is the navigator, correct?

AP. Yes.

JP: I know that many people have tried to talk you out of doing this.

AP: Not all the time.

JP: That’s safe?

JP: That’s safe?

AP: I’m still here.

JP: Does this happen all the time?

AP: Not all the time. If the water is rough, then yes.

JP: Now I understand that your son is a surfer?

AP: Yes. He’s been all over. But he’s stopped now.

JP: Actually that seems more danger to me than speed boating.

AP: Really, why?

JP: Squali.

AP: Squali? Sharks?

JP: Yes. Moving on. When Borg attempted his comeback in 1992, he hired you as his coach.

AP: Yes.

JP: That must have been a fun time.

AP: A lot of fun times.

JP: He only tried for a couple of years.

AP: Less, he really only tried for a few months.

JP: The sport had changed completely when he tried his comeback.

AP: Yeah. We saw each other in Milano and he said he really wanted to do this and he saw my reaction. He said no, I’m serious and I was laughing at him. Don’t laugh at me he said to me because I’m taking this very seriously. Okay. Very serious. Now we take these racquets and throw them away and then we find a good racquet for you. No, no, I want to play with this racquet. We got into a big argument. I said you’re not gonna. No way. No I want to play with this racquet. You cannot play with this racquet.

JP: Last question, what is your favorite restaurant in Rome?

AP: George’s. It is a very important restaurant in Rome